Reading Time: About 6 minutes

I’d never heard of a line search. But the ranger looked very serious when he told me I was needed for one. I soon learned it was a necessary rescue technique to find two of my colleagues who were lost in the forrest.

We had been participating in a team-building exercise in Leadville, Colorado (elevation 10,152 feet). The “we” in this story was a cadre of corporate marketing executives gathered together to discuss “the future” and “synergies” and “team-based ROI.” The year was 1998 and I was still too junior to have much of an opinion on any of these topics, but I was thrilled to get an all-expense-paid trip to the Rockies for a fully-sanctioned summer boondoggle.

We spent the morning gathered in a windowless conference room at the hotel, digesting presentations and discussing “our process.” The afternoon was reserved for an outdoor adventure: orienteering on Colorado’s finest back range real estate. Orienteering is a competitive sport. Equipped with a map and a compass, teams hike as fast as they can to discover control points where they gather codes that prove they made it. The team with the most codes when time runs out wins, but the purpose of the exercise is to encourage collaboration. One player has a compass, the other a map. Together, they must decide which control points to pursue and how to navigate to them.

The first sign of trouble was that we were allowed to pair up into teams at our discretion. That Nick and Mike (not their real names) chose each other was not a surprise. They were fast friends and two of the most competitive spirits in our division.

We had twenty minutes to collect our codes. That’s not a lot of time, and the ranger encouraged us to be smart about our targets. A good number of these targets were spread out within a short range from our base camp. Further out there was a veritable bonanza of targets closely clustered in one small enclave. If you wanted to embrace the exercise in the spirit in which it was intended, you’d stay close to the camp and work your collaborative muscles to make the most of the targets in range. But if you were a daredevil, you’d sprint for that outer outpost and return with more codes than anyone else.

Guess which option Nick and Mike chose.

Most of us returned to base camp 20 minutes later. A few teams bounded back a little after the time limit. We were all in a good mood. We’d had fun. We commiserated about the shared challenges. One team had already bested most of us by a two code margin. Ten minutes had passed and only one team was missing. Nick and Mike. Then thirty minutes passed.

Here’s the thing about a place like Leadville, Colorado: the terrain is so stunningly beautiful you forget that it’s wild, that it’s steep, that it’s out in the middle of nowhere. This was 1998. While most of us had cell phones, few of us brought them along for this exercise. Even if we had them, there was no signal. We couldn’t just call the guys to make sure they were ok. And it was dusk. Soon, they’d be somewhere in the forrest in pitch black darkness. That’s why the ranger was gravely serious when he suggested that no one leave. We would all be needed to do a line search to locate Nick and Mike.

Fortunately, while we were being briefed on the rescue procedure, the two over-achievers straggled in. They were smiling. We were not.

I share this story to illustrate findings from a recently published study in the Journal of Consumer Research which documents a fascinating finding about gender differences in human behavior around the compromise effect.

I have written about the compromise effect before. It is commonly used by marketers in pricing strategies. Imagine a product that has three options: a bare bones version, a deluxe version, and a version in the middle that has bits of the deluxe but costs only a little more than the bare bones. That middle option is known as the compromise. It’s not the cheapest, but it’s got enough premium add-ons to make an average consumer choose it.

Until the current study, we’ve always considered the compromise effect in isolation, with an assumption that the decision is being made by a solo individual. But a lot of decisions are made by couples or small groups. Imagine a married couple shopping for a home, or a management team deciding on which strategy for a company. Does the compromise hold up when more than one person is involved in the decision? And how does gender affect this collaborative decision-making.

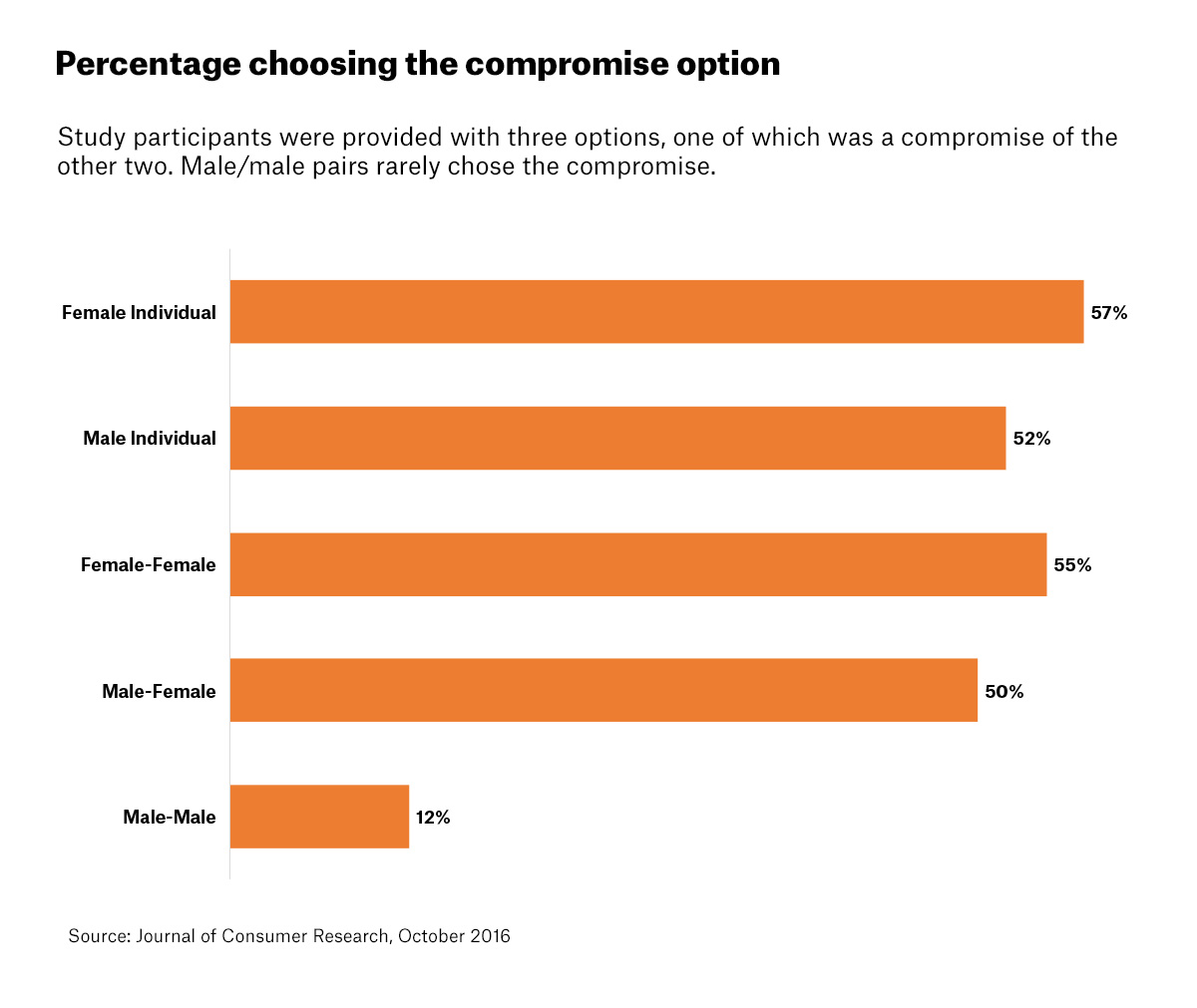

It turns out that the compromise effect dominates in every instance but one: when the group is entirely comprised of men. That’s right, in the comprehensive study “Men and the Middle: Gender Differences in Dyadic Compromise Effects” authored by Hristina Nikolova and Cait Lamberton, men in groups favored extreme choice options most of the time. Even more interesting is the fact that men in groups rejected the compromise option more than men individually. In fact, there was no significant statistical difference in choice between men alone, women alone, women in groups, or mixed men/women groups. Only in male-male pairs did the preference for extreme options dominate … and by a wide margin.

The findings are not entirely surprising and they help to explain why Mike and Nick opted to go for broke while other mixed gender teams took the safer “compromise strategy.” We’ve read many stories in the business press of male executive teams that opted for the riskiest of management strategies—often to the detriment of investors—because of this tendency to swing for the fences in spite of the odds. Like Nick and Mike that day in the Colorado Rockies, men are driven to reject compromise when they make decisions with other men. The fascinating aspect of this new study is just how quantifiably significant this tendency is, and how consistently observed.

As a red-blooded American male, I confess that I am not immune to this behavior. It’s not always about ego. Strange things happen when you ask a male friend to help you choose a big-screen TV. There’s an intoxicating rush experienced by the shared desire to “go big or go home.” You end up going home and explaining to your wife why the TV is too big for the intended wall.

In two days time, America will choose a new President. The election cycle has gone on for so long that most of the country (myself included) just wants it to be over. The intensity of the media coverage and the shocking depth of insults and personal attacks from both sides has jaded the American public. A recent Pew Research study found that more than a third of Americans are “worn out” by election conversations in social media. I also believe it has pulled our political discourse even further to the extremes. Compromise has become a dirty word, disdained by both parties. But on November 9th the real work of getting things done for the next four years will be before us, and compromise will surely be necessary.

There is currently one woman for every four men sitting in our Congress: 104 are seated in the House of Representatives (about 19%) and 20 occupy the Senate (20%). Given the findings of this latest research on decision making, does it surprise anyone that we are so focused on extreme positions and an absence of compromise? For example, consider the Senate Judiciary Committee’s extreme position not to consider Merrick Garland, the President’s nominee to the Supreme Court. Besides the GOP bias of that committee, it is also worth noting that it has twenty members and only two of them are women.

While gender has surfaced as a significant issue at many moments in time during this election cycle, perhaps the focus on its impact over the executive branch is misguided. Whether our next president is Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump, the measure of success for either candidate will revolve around their ability to advance their platform. Sadly, with only one in five legislators a woman, compromise will probably remain elusive.