Reading Time: About 7 minutes

Protests in major American cities. A nonstop tsunami of stories stacked at the top of every media outlet. The outcome of the 2016 presidential election refuses to be ignored. Nowhere more so than on social media. Both Twitter and Facebook posted record-breaking traffic gains. Use of the platforms may not have been the only surge. Many users are saying that they have experienced increased clashes with friends and family over the outcome of the election. A sizable number are confessing to blocking and unfriending people, or dropping off social media platforms altogether. A recent NPR story went so far as to claim that social media may have ruined the election because of the vitriol it created between “friends.”

Social media platforms like Facebook have revealed curious human behavior. Why do people feel the necessity to attack and disparage their friends on social media channels when they disagree with a political point of view? What do they hope to accomplish?

The logical answer is to say that people want to educate or to provide an alternate point of view. If Jane says that Bob is unworthy of public office, Dan points out Bob’s accomplishments as a rebuttal. His objective is to invalidate a false claim and to perhaps persuade Jane to reconsider her opinion of Bob. This scenario certainly unfolds in social media, and I can say that I’ve participated in comment streams where friends of mine did just this … with inspiring sincerity and decorum. But I would also argue that this scenario is the exception and not the norm.

Here’s the more common scenario:

- Jane

- Donald trump is unfit for office.

- Bob

- LMAO. You liberals love to whine.

Invective ensues until one party or both unfriends the other. It’s hard to argue an educational or empathetic motive here. This is good old-fashioned shaming. A practice that has become so rampant that it’s having an unprecedented impact on personal relations.

A dear friend of mine confided to me that she was considering blocking her father from her social media feeds. It pained her, but she could no longer tolerate the battery of his posts expressing opposing and (in her mind, at least) offensive views, nor his onslaught of comments to the posts she made about her own political views. She told me that she had a lot of respect for her father and she feared that more exposure to this dialog would erode this respect.

155 years ago, Americans lamented the battle of bullets between brothers on the Mason-Dixon line. Today, we shake our heads at the battle of barbs on the digital divide.

I experienced this first-hand on Wednesday morning. Like half of American voters, I was disappointed. I expressed this disappointment in a Facebook post. Within minutes there were three negative comments from “friends”, one telling me to “stop being a crybaby.” I did not unfriend them, but I did delete the comments. The space on my Facebook wall is mine. I reserve the right to curate it as I wish. And I gave my acquaintances the benefit of the doubt in this case. I don’t think they are bad people and I don’t think they think ill of me. As much as I needed to express my disappointment, they needed to express their resentment.

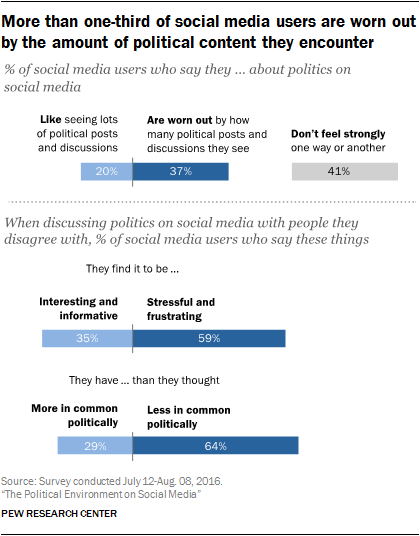

In a recent study by the Pew Research Center, only one in five Americans said they like seeing political posts on social media. Over a third said the content wore them out. 60% said that discussing politics with people who have opposing views is “stressful and frustrating.” And almost 2/3 said that the dialog made them realize that they have less in common than they thought. With such findings, you have to ask why anyone engages in such conversations on social media at all.

Most of us have been counseled to avoid politics and religion in mixed company. Why are these topics a dangerous third rail? Or, perhaps more to the point, why do they invite unsolicited debate and relentless trolling? Why can a simple post about a political candidate lead to the end of an online friendship in a way that a post about one’s love affair with a television show does not?

First to blame is positivism. The name is misleading. It is not about being happy and optimistic. Rather, it is a centuries-old philosophical mindset that divides the world into facts and values. Kwame Anthony Appiah describes the mindset and its influence over political discourse beautifully in his book Cosmopolitanism:

There are facts and there are values. Check. Unlike values, facts—the things that make beliefs true and false—are the natural inhabitants of the world, the things that scientists can study or that we can explore with our own senses. Check. So, if people … have different basic desires … different values … that’s not something that we can rationally criticize. No appeal to reasons can correct them. Check. And if no appeal to reasons can correct them, then trying to change their minds must involve appeal to something other than reason: which is to say, to something unreasonable … Checkmate.

Use this model to evaluate someone who expresses their support for a political candidate online. While there may be certain facts that led up to this moment of endorsement, the act of posting is probably more tied to the poster’s values—an identity alignment. He or she stands for what I stand for. No amount of facts or reasoning is likely to change this connection between value and candidate, unless of course the link is weak and the poster is soliciting feedback to help in making a decision. This is rarely the case.

Yet we in the west can’t help but try and reason to the unreasonable. We feel driven to stamp out opposing views with facts when values are the true drivers. This is perhaps what all the pundits got wrong in the election this year. They focused on the facts related to gender and race and geographic location and overlooked the simmering values and voter identification with those values that were truly at play.

And if reason won’t work, then let’s get to shaming. Your endorsement of a candidate isn’t really a fact I can prove or disprove. It’s a value. I have no real way to prove or disprove it. So, instead, I attack you. “Well … your mom is ugly.”

Second, the trolls surface because of a little-discussed phenomenon called persuasion knowledge. What is it? We often rely on three bodies of knowledge to make decisions in our daily life. The first is topic knowledge—how much we actually know about the subject we’re considering. You post your support for Measure X. I see your post, but maybe I don’t really know anything about Measure X. I have to access another body of knowledge to engage with you, so I turn to messenger knowledge—how much I know about you. I might see your post and think, “I don’t know anything about Measure X, but I do know Linda. And she’s very fair and smart.” Done. You might be persuaded to think more about Measure X. However, what if Linda is always posting political messages on social media and they’re constantly on the opposite side of your values. Now, if you don’t know anything about Measure X your knowledge of the messenger (Linda) deeply colors your perspective, and perhaps riles you up to respond—not because of a strong feeling about Measure X but because of a strong feeling about Linda.

But there’s another body of knowledge—persuasion knowledge. Here, we rely not on what we know about the topic or the seller but about what we know about attempts to persuade us. Persuasion knowledge is all about motive, or rather what you perceive to be the motivation for the post. It is here that much of the nastiness and unfriendliness unfolds on social media.

On any single day, you are bombarded with thousands of persuasion attempts—everything from trying to sell you a hamburger to encourage you to wear a condom. You are also bombarded with a variety of persuasion methods. Some are soft-sell, some are hard-sell. Some are overt, some are sneaky. With each attempt your knowledge of how people and institutions are trying to get you to do things grows. You become savvy about motives and tactics. In fact, because of the onslaught that we face each day, many of us are hyper-sensitive to motives and tactics. One reason a lot of advertising is ineffective is because the modern consumer sees through the motive and disregards the message.

James posts his concern about Donald Trump’s comments about women on Facebook. Richard is a Trump supporter, so he is pretty knowledgable about the topic. He’s also known James from childhood, so he has a solid base of knowledge about the messenger. Richard might know that James is a Hillary Clinton supporter. Yet, that’s not enough to send him over the edge. Instead, the reference to Trump’s comments about women triggers persuasion knowledge. Richard is incensed. He believes that the media is taking something from the past out of context and smearing his candidate. Even though Richard is a perfect gentleman around women, he feels that James is trying to unfairly persuade him (and others). Get ready for a snarky comment…

I am giving a lot of trolls unreasonable empathy. There are people who enjoy dispensing agitation—who like playing “devil’s advocate” or who feel a need to litigate and prosecute in the court of social discourse. But there are other forces at work that are worthy of further study. While some argue that social media is encouraging more connections between people it is also nourishing bad behaviors. Our keyboards and our touch screens are a barrier to sensitivity, empathy and context. They provide an illusion of detachment—a fleeting sense that what we post is harmless. That sense deteriorates in an instant when a comment seems to attack our deepest values or allows our minds to presuppose a motive that might not exist at all. Even when people don’t act on these impulses, the signals can fester over time and color our perceptions of the messenger. “Sheila posted a lot of Trump messages on Facebook. I guess I was wrong about her.” Meanwhile, Sheila is the same co-worker who looked after your cat when you were in the hospital, and always stops by your cube to catch up on your life. Which signals should you judge? The ones you find on Twitter, or the ones you find in life.

But your mother was probably right. Best not to discuss politics in mixed company.