Reading Time: About 5 minutes

Two weeks after Americans elected Donald Trump to be their 45th President, many are still wondering how the polls got it so wrong. They question the logic of the outcome. How could a man with the highest negative opinion rating in Presidential history win the ultimate contest? Why did almost half of voters cast a ballot for a candidate who made openly misogynistic and racially divisive statements? How did a billionaire become the hero of the poor?

I will leave the political analysis of the 2016 Trump campaign for others to debate. I am more interested in the shift in American ideology that we just witnessed. In 2016, Americans voted for regressive change. The platform underpinning the Trump presidency is not grounded in innovation or bold experiments in public policy. Instead, it is about putting things back the way they were. His campaign slogan says it all: make America great again.

Several forces are at play. In my consumer research over the past few years I have observed an uptick in nostalgia across demographics. I wrote recently about Millennial nostalgia for the 90s, breathing life into brands of the era and influencing media and popular culture. For example, Friends is currently one of the highest trending titles on Netflix. But an increased gravitation toward nostalgia is not enough to explain the outcome of November 8, 2016. There’s little to suggest that Trump’s rhetoric evoked the same halcyonic longing that Ronald Reagan’s “Morning in America” so perfectly summoned. Reagan’s campaign painted a picture of a shining city on a hill. Trump’s campaign mostly pointed a finger at our dystopia.

I believe another force is driving the American mindset—a force much like nostalgia because it shapes ideology from past experience. However, unlike nostalgia, this force relies less on the bittersweet pains of memory and focuses instead upon our collective sense of security in re-establishing norms and control. It’s a force with a funny and counter-intuitive name, like much in the domain of academic research. It is called System Justification Theory.

System Justification is an ideology in which people prefer the status quo to any form of change. At first blush, the outcome of 2016 seems to be far from a mandate for the status quo. Trump’s victory was won on promises of sweeping change—the repeal of the Affordable Care Act, the reversal of US involvement in the Trans-Pacific Partnership, and exits from the Paris Climate Agreement and the Iran Nuclear Accord, to name a few in the campaign platform. Yet, these changes all represent reversals from the progressive agenda of the sitting administration. In effect, voters have rejected Barack Obama’s vision and called for a return to a system of the past.

System Justification has fascinated social science researchers because of its particular impact on the disadvantaged. Numerous studies have observed the phenomenon in which people in so-called “out-groups” prefer a status quo that renders them inferior and puts them most at-risk. Oddly, these out-groups also hold favorable opinions of higher status social groups that are more advantaged by the status quo. In the case of 2016, this phenomenon is readily observed by economically depressed social groups that have strongly identified with Trump.

The theory helps to explain the dramatic shift in our cultural tone. Progressives have been alarmed by what appears to be a retreat to nationalistic impulses, latent racism, and intolerance. Americans have experienced an apologist surge against political correctness, much of it driven by systemic justifiers who have rallied around Trump’s projection of power—his social status, prestige, and dominance; his apparent disregard for the required manners and decorum that typically accompanies the office. The most common words of validation from a Trump supporter is that “he speaks his mind.”

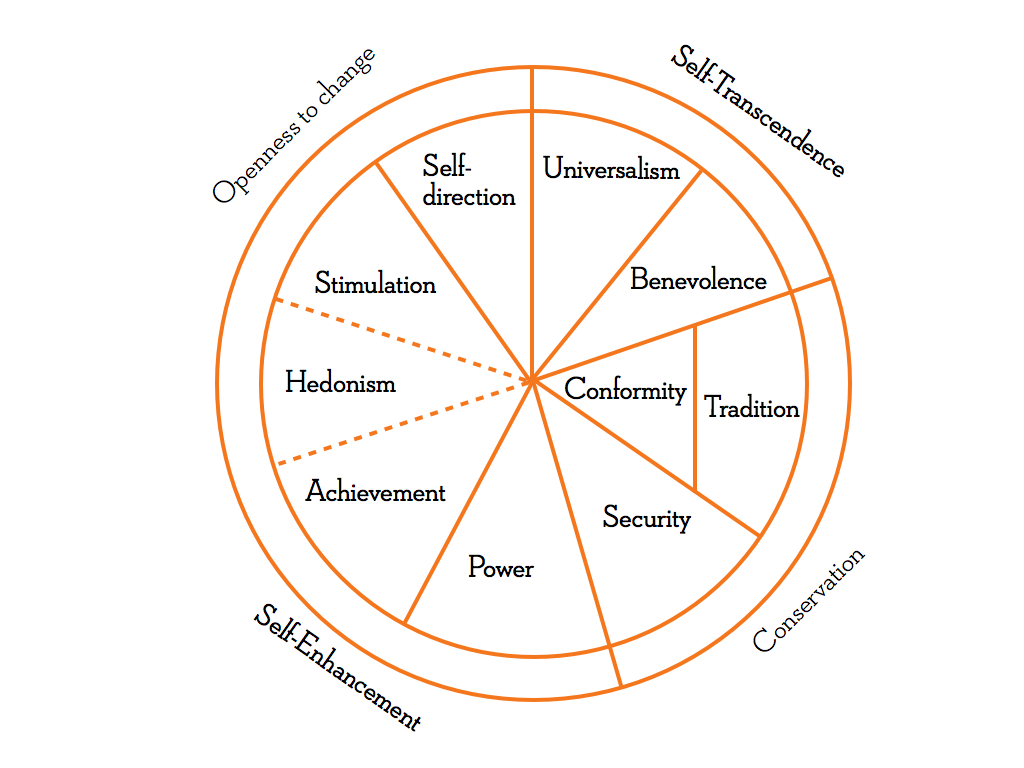

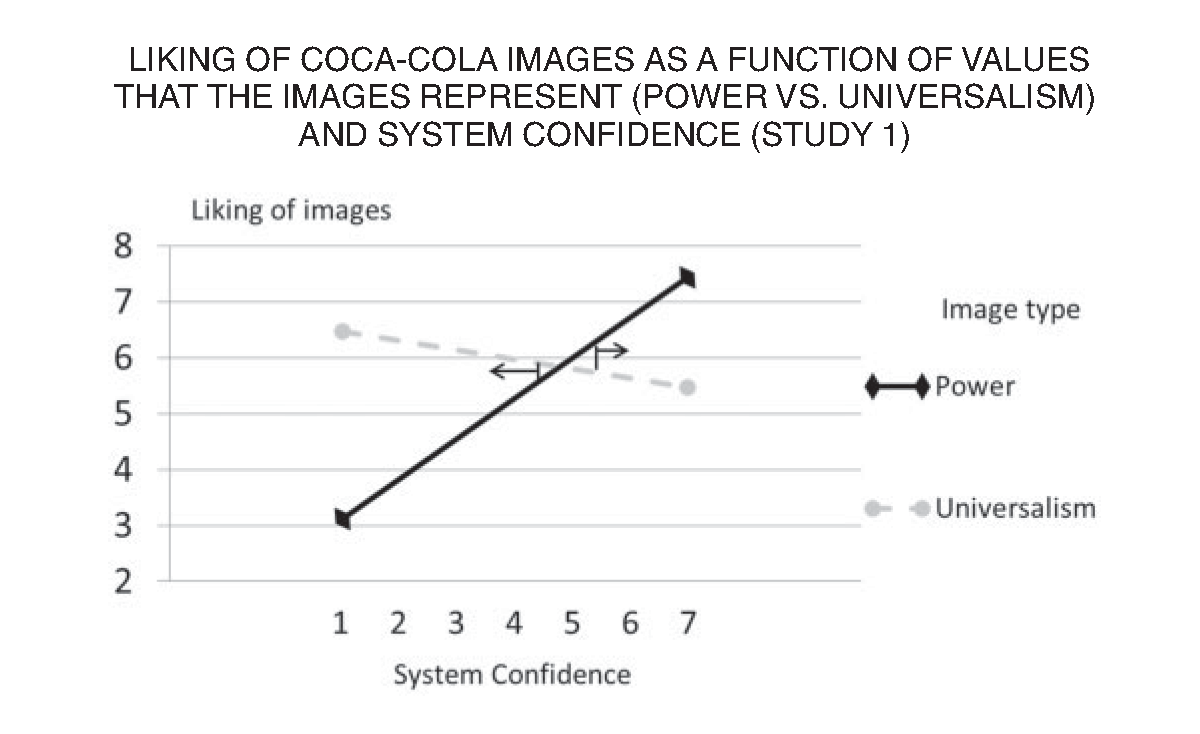

The link between system justification and overt power is not a coincidence. A 2015 study in the Journal of Consumer Research found a clear structural relationship. In a series of experiments that focused on consumer relationships to brands, the study found that high system confidence correlated strongly with a power-driven ideological view of America. The study relied upon a prolific body of social science research that focused on measuring human value orientations. Pioneered by Dr. Shalom Schwartz to understand ideological differences between nation-states, the research uncovered ten universal human values that have been observed across cultures and in numerous socio-economic settings. The structure of these value orientations is what makes the research so compelling. Each value sits on a circular spectrum; each node with a 180-degree corollary.

For example, people who are oriented towards hedonism tend to have a dim view of conformity, and vice versa. Achievers typically have less in common with benevolents. And power-seekers rarely align with universalists—people with a value orientation that is driven by understanding, appreciation and tolerance. The universalist ideology is drawn to issues such as the well-being of society as a whole, protection of nature and the environment, social justice and the pursuit of peace. Sounds an awful lot like a progressive agenda, doesn’t it?

Source: Journal of Consumer Research, Volume 42, Issue 1

The divide between those who value power and those who value universalism isn’t so black and white. In fact it’s common for most people to embody some aspects of both value orientations. The revealing aspect is the link between those who skew towards a power worldview—a worldview that seeks greater control over people and resources—and a desire to retain a known social order.

This drive to get back to “the way it was” may have a lot to do with the massive disruption we have experienced in a very short time. Economist Thomas Friedman believes the world took a massive turn just nine short years ago. Writing for The New York Times, Friedman has argued that “2007 may be seen as one of the greatest technological inflection points in history.” He provides ample evidence in support of his argument:

Steve Jobs and Apple released the first iPhone in 2007, starting the smartphone revolution that is now putting an internet-connected computer in the palm of everyone on the planet. In late 2006, Facebook, which had been confined to universities and high schools, opened itself to anyone with an email address and exploded globally. Twitter was created in 2006, but took off in 2007. In 2007, Hadoop, the most important software you’ve never heard of, began expanding the ability of any company to store and analyze enormous amounts of unstructured data. This helped enable both Big Data and cloud computing. Indeed, “the cloud” really took off in 2007.

For some, such massive innovations are symbols of progress and the potential to create opportunity in the world. For others, they are a source of great uncertainty and insecurity. To them, these technologies have unleashed new security threats, displaced employment, and accelerated the pace of daily life (not to mention the news cycle that reports on it).

We should expect that these conflicting views will permeate our cultural landscape for some time to come. The tension of power vs. universalism will surface in the narratives of our media content, including the advertising that lures us to the cash register. Some will over-compensate and others will follow whatever trend seems to resonate in the moment, but the real proof will be found in the hard decisions–the ones that weigh the pros and cons of disruptive change vs. a new interpretation of the secure status quo.