Reading Time: About 5 minutes

In 2009 America bid a final farewell to its “most trusted man,” Walter Cronkite. Though not always liked, Cronkite was nearly always respected. He embodied a bygone era in journalism when the national news media gained consumer loyalty and credibility because of its dedicated pursuit of facts, objectivity and perspective. It was a time when the tech darling of the day (television) provided a massive platform for audiences to connect with a single, authoritative voice that helped them curate the events of the day. This loyal following crossed all generations and cast a halo on its network. If the news was on CBS and Cronkite reported it, it had a preferential seat at the table of our judgment.

Less than a decade later, none of the brands in the news media earn this blind trust from a majority of Americans. No single journalist carries Cronkite’s mantle. And the next generation audience is not only skeptical about the national news media, they’re easily duped into believing the fake news they stumble across on social media.

The last point is particularly troubling in the context of the recent election cycle. Facebook and Google are under increasing pressure to reign in fake news sources, which many believe had an unjust influence in political discourse and possibly the election itself. Advocates want the social media juggernauts to protect the modern news consumer from influences they apparently cannot perceive on their own.

A recent Stanford University study found that a majority of middle school, high school and college students could not identify the difference between a mainstream news source and a fringe source. More than half concluded that a story by an organization classified as a hate group was more reliable than a similar story published by a decades-old, nonpartisan and very well-respected professional organization. And more than 80% of middle school students believed that sponsored content on a nationally recognized news site was a real news story, despite branding that labeled it “sponsored content.”

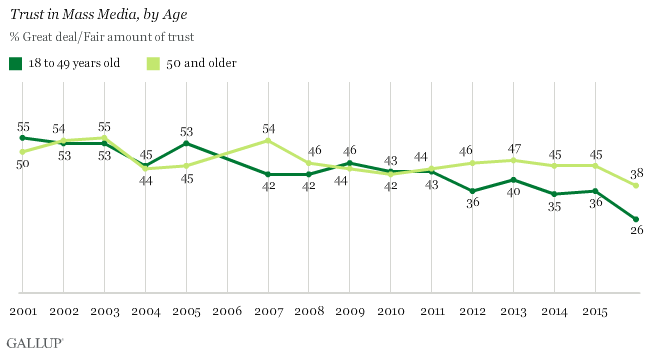

According to Gallup, only 26% of Americans 18-49 trust mass media today, the lowest score since Gallup began tracking the statistic. For some perspective, that figure was 55% just 15 years ago.

This is a case of an industry-wide brand problem. The news media has lost two critical drivers of brand credibility: trust and expertise. The latter is critically important. A 2004 study in the Journal of Consumer Research found that consumer perceptions of expertise (the degree to which the consumer perceived the source to be competent and knows what they are doing) had the strongest influence over their perceptions of trustworthiness.

A study by the Pew Research Center in July of this year found that consumers today trust the news they get from a national news organization only slightly more than the news they get from family friends and acquaintances (18% for national news organizations vs 14% for friends, et al.). And the culprit appears to be perceptions of bias. Only one in five of those polled said that they trust news organizations to deal fairly with all sides. Concerns about bias were pronounced amongst all political ideologies.

The ramifications of this distrust are staggering. The news media has played a pivotal role in American opinion formation since colonial times. Recall that Thomas Paine was a pamphleteer. Ben Franklin published a newspaper. Today, both would likely be viewed as “biased intellectuals” and they’d have a hard time competing with the populist conjecture that some fool posted on Twitter and Facebook.

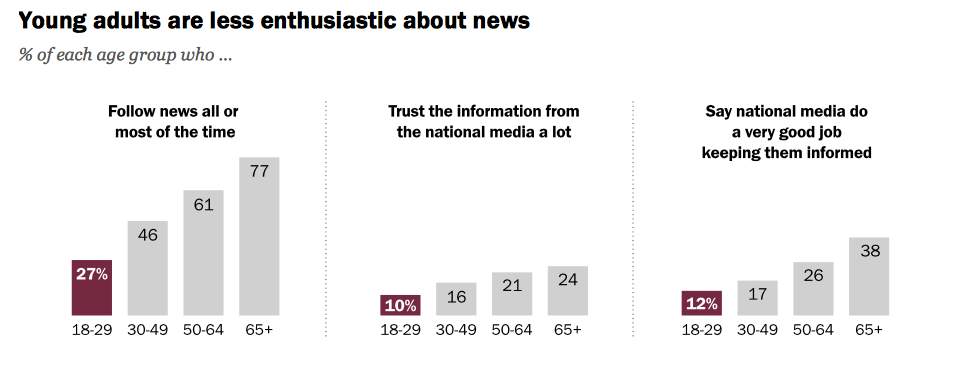

I wish I could say that the future looks bright, but the Pew study doesn’t offer many glimmers of hope. Only 27% of Americans aged 18-29 follow news all or most of the time, compared to 46% for age 30-49, and 61% for those age 50-64. The gaps between generations is common, but not at these margins. Further, only 10% of 18-29 year olds say they trust the information from national news media, and 12% gave the national news media a thumbs up for the job they do in keeping the nation informed. In any other business, this would pave a path to bankruptcy.

Yet, those same young Americans are the most likely to get news online. The shift from traditional media has been accelerating over the past decade across every demographic. Four out of ten Americans get their news through a digital device today vs 57% who rely mostly on TV. But half of those 18-29 keep up with the news online, more than any other segment.

It seems some national news outlets are taking steps to counteract the decline of the industry brand by adopting an “if you can’t beat them, join them” philosophy. In October, CNN poached BuzzFeed’s investigative political research team, known as the K-File, led by reporter Andrew Kaczynski. In the storied world of professional journalism, the news was a mild shock because upstart BuzzFeed is more often (erroneously) associated with click-bait and pop culture fodder than it is the rigorous establishment journalism espoused by an institution like CNN.

CNN’s move may be a step in the right direction, but it’s only a band aid; a slight course correction that acquires a proven audience in a high-value demographic. It doesn’t solve the underlying problem.

When we talk about the news, we normally add a word to the identifying phrase: the news media. In fact, many shorten the entire industry to the word media. But the news media has failed to reinvent itself with the media of the day. Its forays into social and digital media have sought more to promote programs on legacy channels than leverage the media’s own unique capabilities and its powerful relationship with new audiences. With all due respect to John King, a man and a touch screen map is not an innovative use of media. We need journalists who understand the closeness they can provide between their audience and the world at large. Cronkite purposefully slowed his speech to 160 words per minute so that more people would follow and engage (for perspective the average person speaks in excess of 200 words per minute). While that would probably not work today, there are ample tools in our new media that can serve the same purpose. Where is the Cronkite of Facebook Live? Who is the Anderson Cooper of Snapchat? Why is there no equivalent of Barbara Walters on YouTube?

Part of the problem lies in the way that we raise and groom today’s journalists. Today’s star reporter for the New York Times probably started by writing obituaries for an obscure local paper. The woman anchoring the national news might have started doing weather in a local market. Journalists grow in a farm system that favors traditional media. We need to start grooming journalists who grow up in a social media framework.

Winning the trust of the next generation news consumer will require a full-scale disruption of the way we gather, report, authenticate and share news content. Technology certainly plays a role in this disruption, but so too do the human practices of reporting and engaging with audiences. It’s unlikely (but not impossible) that Uncle Walt would crush it on Vice the way he did on CBS. But it’s very likely that a reporter on Vice could someday gain the wide public trust of Cronkite. The model must change, and so must the players.