Reading Time: About 8 minutes

America loves a challenger. Indeed, some are explaining the election of Donald Trump as a result of our abiding admiration for those that thumb their nose at the establishment. As a nation, we have been glorifying challengers since the day those daring patriots dumped the King’s tea into Boston harbor. Today, entrepreneurs point to Steve Jobs, who told us it was “more fun to be a pirate than join the Navy,” and who advertised his signature product by celebrating “the crazy ones, the misfits, the rebels, the troublemakers, the round pegs in the square holes, the ones who see things differently.”

Over my career, I have gravitated towards challenger brands because they are fun. They’re helmed by risk-takers and wide-eyed contrarians. These are the businesses and business leaders who believe they can (and often do) change the world. I have written about these brands a lot, and I have admired the pioneering work of Adam Morgan, who has meticulously studied challengers and made many in the business community wake up to the power of challenger behavior. And, I have sat with many a client who either believes that her company is a true challenger or who desires the opportunity to develop a challenger culture.

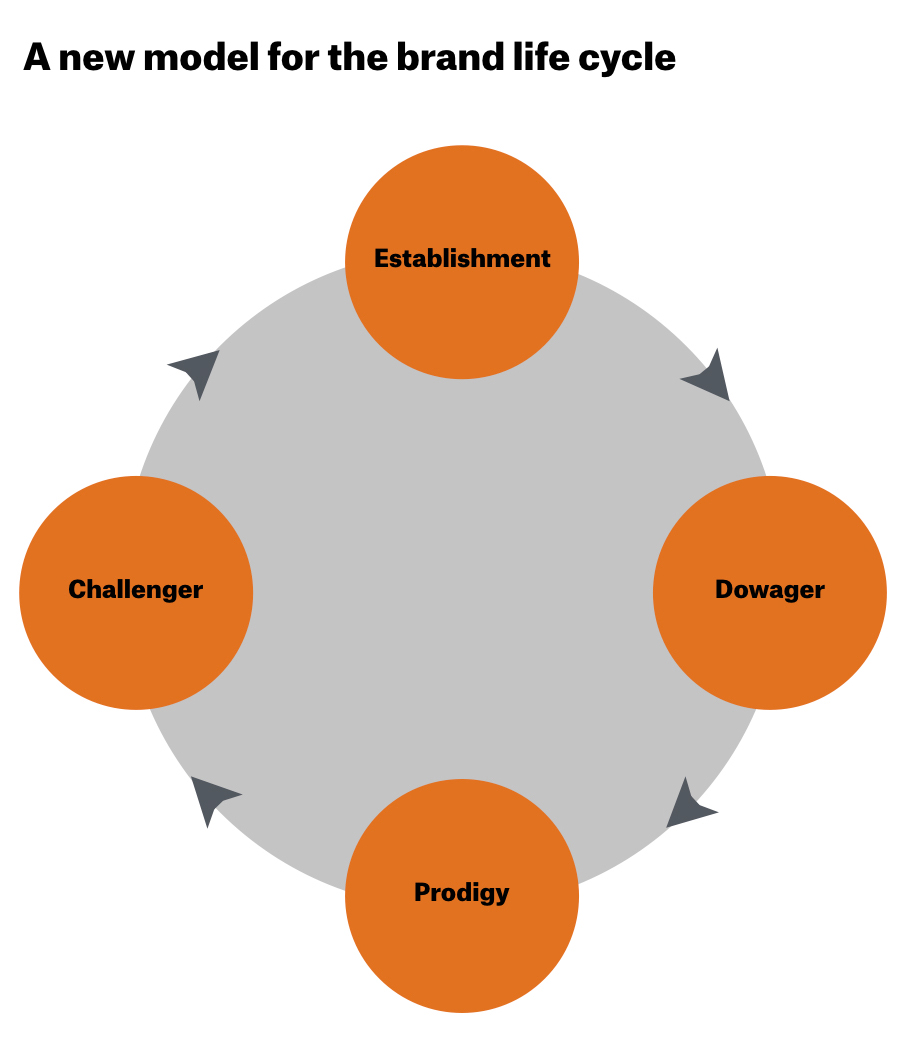

The broad enthusiasm for challenger brands makes it easy to conclude that becoming a challenger should be the goal of every company. Such thinking is a serious mistake. Being a challenger is a state of mind that accompanies a phase in a brand life cycle.

Challengers can’t go on forever challenging. Well, I suppose they can, but at some point their challenge should result in a victory, otherwise they may well be losers, martyrs or outlaws. “Challenger” is a mindset, and mindsets evolve. That’s not to say that companies should shy away from constant change, but constant change is different than occupying a challenger mindset. We in the management community haven’t spent enough time thinking about this natural maturation and evolution of challenger brands.

In the second act of the Tony-award winning musical “Into the Woods” Stephen Sondheim asks a simple question: what happens after “ever after?” What happens after the prince saves the princess and they settle down to start a family of their own? The same question holds true for a challenger brand. If it is successful, what happens next? If it gains the #1 share of the market or the most influence over our minds, shouldn’t it at some point become an establishment brand?

I mentioned Steve Jobs because Apple is the exemplary reference for what it means to be a challenger brand. Yet I would argue that today Apple is very much an establishment brand. Though Android has the largest share of the smartphone market, Apple is the referential brand that all others (including Android) strive to beat. Depending on the whims of the stock market, Apple is the world’s most valuable company. It is the over-used poster child of best-in-class brands, so much so that it influences brands in far distant product categories. While one could argue that Apple is the result of a challenger mindset, its current behavior is more Navy than pirate. Its operating reputation revolves around a circle of tight control, secrecy and strong-arm tactics. And, it is riding the wave of innovation that occured nearly a decade ago.

If a challenger brand’s vision for the world resonates, people will believe it and follow it and elevate it from an “alternative” perspective to the new status quo. There’s no shame in that success. But becoming the establishment scares the rebels within challenger cultures because it feels like selling out. The act of rebellion that drives successful challenger brands is intoxicating. It involves breaking rules and norms, unsettling market dust, squashing sleepy bureaucracies. It is more fun to be a pirate than join the Navy, yet the spoils of being a successful pirate eventually tame this desire to rebel. Why spoil a good thing? Even a pirate will succumb to a routine if that routine leads to success.

Brands ascend and evolve in a cycle. The challenger phase is the most cherished in that cycle. It’s the era with the most momentum—when boundless internal energy summons a groundswell of external enthusiasm. Employees of the brand sweat their lives to achieve the impossible. Consumers become cultish in their loyalty. And investors take risks they might otherwise shun because the scent of a massive financial return lingers in the air. The challenger phase of a brand is when the flame burns the hottest.

But it can’t go on forever. When a challenger achieves the goals inherent in its vision it will inherit a leadership position in its category. At that point, the management focus will change by neccessity. Writing in his 1988 management classic, Managing Corporate Lifecycles, Dr. Ichak Adizes called this the crisis of the “Go-Go” or adolescent company and it is usually a pivotal moment for the leaders of the rebellion.

Founders and change-leaders can be very good at disruption but terrible at sustainability. The vision that ushered the brand to phenomenal growth doesn’t always support a steady state. Quality must be maintained. Customers must be serviced. Employees have to be recruited and retained to prevent the vision from becoming a fad. The promise of upsetting the old order of things has to be replaced by a commitment to uphold the new order.

Employees come and go. Those with the real challenger spirit might jump ship to another vessel with a leader aiming to stir up another market. The challenger personalities that stay can sometimes feel repressed by the new pressures of a “grown-up” company. Many want to sustain the challenger culture inside, but this mindset can lead to corrosive nostalgia, a perpetual reminder of the way things were in the “old days”.

It’s no surprise that founders and pivotal startup teams so often exit their companies after they make it big. It’s not just because they can afford to stop working. It’s because the company transitioned from challenger to establishment. The skills required to sustain an establishment brand are different.

Establishment brands can be truly noble beasts, engendering tremendous pride in the cultures that grow and extend them. History, and the markets, reward establishment brands more than any other type of brand. Disney, GE, Coca-Cola, Ford—these are brands with proud internal cultures. They are also consistent business performers. They are the gold standard. They are the benchmark that competitors (including rambunctious challengers) use to judge their own success. An establishment brand is not something to be loathed. It is the vessel captains of industry sail to serve the world. Apple is one of the world’s most beloved brands, as is Google and Facebook. Each is now an establishment brand. Firmly so.

As challengers nip at their heels and disrupt the order so carefully maintained by establishment brands, some establishment brands will inevitably cede ground. Many become dowagers. My mentor and friend Dennis Rook introduced the marketing world to the concept of the “dowager brand” in an article he co-authored with Sidney J. Levy. Rook and Levy defined the dowager as a brand that enjoys “elevated, although perhaps slipping, status amongst its competitors.” Dowagers are still very much a point of reference in their market, though they are often called “old” or “out of touch.” Microsoft is the dowager of the tech world today. While Microsoft continues to be a dominant force in many markets, especially enterprise computing, you’d be hard-pressed to find someone in their 20s who would view it in the same way that they do Google or Apple. Microsoft earns respect because of what it has accomplished and because it is still strong enough that it cannot be ignored, but fewer today see it as the brand that will shape and define the industry. This is the reputation of a dowager.

Dowager brands possess power and many advantages. Dowagers are usually linked to an empire and perhaps a dynasty. The dowager has high awareness and familiarity, though its brand image may have declined somewhat. People know the dowager, they just might not believe the old gal has much of a future. They’re already contemplating a world without her, or a world in which she recedes quietly into a walled fortress, pampered but inconsequential. Yet dowagers produce offspring. Like any royal family, these priviliged progeny can resuscitate the family line. Dowagers can beget prodigies.

The prodigy brand need not descend from a royal line, but prodigies that are birthed by a dowager or establishment brand often have a strong advantage. Microsoft begat Xbox, which is a dominant force in the video game market. Microsoft also begat Surface, which is attempting to restore the family honor in the device market. Xbox and Surface enjoy advantages that other prodigies do not: ample resources, preferred access to industry infrastructure, and, of course, the family name. But the prodigies we tend to love the most are those that possess the underdog’s genes—the ones that often lead a challenger wave. These prodigies are startups.

Mark Zuckerberg. Sara Blakely. Elizabeth Cutler and Julie Rice. Each of these individuals started something from nothing but an idea. When they began their journey they didn’t know their business concept would eventually grow into a challenger brand. What they had was a vision and grit. As a result, the world soon came to know Facebook, Spanx and SoulCycle.

Prodigy brands can emerge anywhere—inside the castle of an establishment or outside of the great wide dominion. A lot of prodigy brands don’t start out to be challengers. They want to be successful, but they’re focused on building the better mousetrap, chasing the windmill of a problem that needs to be solved, or experimenting again and again with a concept that could be just right. Until one day, the tide changes and they’re suddenly moving faster than they imagined and they realize they can ride this wave into a leading position in the market.

A lot of prodigies flame out, consumed by their own energy. Some become enfant terribles who believe their own press and implode in a burst of their own arrogance. Others waste away on over-indulgence from their initial successes, refusing to adapt and grow because the initial idea worked so well. Only the chosen few prodigies rise up to the rank of challenger and give the existing establishment a reason to worry. When those prodigies were birthed by an establishment or dowager brand, great drama ensues. Kodak developed pioneering digital imaging technology. Its digital camera platform was a prodigy and heir to one of the 20th Century’s greatest establishment brands. But Kodak’s desire to maintain its legacy empire hampered its own future. It didn’t have time to become a dowager. It went straight to bankruptcy. Today, others profit from the potential of Kodak’s once-prodigious offspring.

It’s all good and well that we relish the challenger saga. It’s as timeless as Disney’s well-trodden hero’s journey. Yet we must not ignore the fact that the challenger is but a chapter in a life cycle. Great challengers must become establishment brands and reign with honor and prosperity. Sure, the challenger spirit can continue to surge within an establishment brand for a time, but that challenger mindset will soon create conflict in a brand that is governed by markets and increasingly preoccupied with retaining its inheritance.

Just so, great establishment brands will eventually become dowagers. Nothing lasts forever. But a dowager has certain advantages and she can bless prodigies that inspire the next generation of challengers. And the cycle continues. As managers and observers of brands and marketing and the world of business, we would do well to consider the entire life cycle rather than fetishize the never-ending spirit of the challenger. Each stage of the life cycle offers unique advantages, distinct management challenges, and its own potential for success.