Reading Time: About 8 minutes

I am reading The Great Gatsby to my daughter Jordan. A few nights ago, after we finished the chapter in which a drunken party-goer crashes his car in a ditch outside Gatsby’s mansion, Jordan said, “he should have taken an Uber.”

In explaining why he couldn’t, it hit me that the fictional tale of Gatsby occurred nearly 100 years ago. There’s a mental block in my head that refuses to imagine events of the 20th century being so far back in time. When I was Jordan’s age, it felt like the ghosts of the Roaring Twenties were still fresh and lively in American life, though of course they were always at least two generations behind my own.

This reflection on Gatsby made me consider something else: the state of the American Dream. Gatsby, both the character and the novel, is the embodiment of that narrative: upward mobility nourished by abundant opportunity and democratic freedoms. For many generations, these ideals were self-evident, pulsing under the surface of American life so naturally that to assert anything other than their certain truth was radical blasphemy. The American Dream has so permeated our culture that it became a failsafe for marketers. If you ran out of ideas for your campaign, you could always return to Americana. It has been the safe retreat for marketers like Coca-Cola, Chevrolet, Disney and McDonald’s.

But times have changed, and The American Dream as a brand narrative may be losing its relevance. Or perhaps it is merely changing, too. Brands should take note.

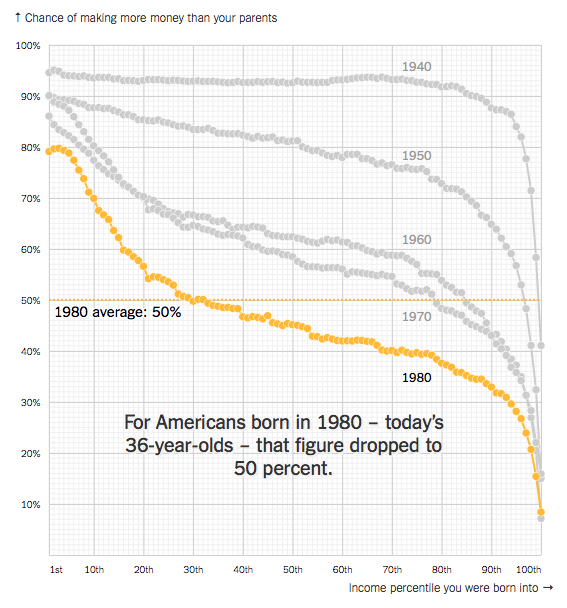

In December 2016 David Leonhardt published an eye-opening op-ed column in The New York Times that revealed some troublesome fractures in the promise of the American Dream. He shared data compiled by a team of economists who used decades of real tax records to ascertain the economic mobility of Americans by generation. Their data confirm what many have speculated for years: that young Americans today are unlikely to out-earn their parents during their lifetime.

The statistics are sobering. Americans born in the 1940’s were almost 100% likely to out-earn their parents (granted, many of their parents endured The Great Depression). The children of the 1950’s had about a 79% chance of out-earning Mom and Dad. The numbers decline for children of the 60’s and 70’s, but most Americans born into those decades still were assured that they would advance economically better than their parents. The picture is more bleak for Millennials. According to the study, “For babies born in 1980—today’s 36-year-olds—the index of the American Dream has fallen to 50 percent.”

Source: New York Times

From a purely socio-cultural perspective—through the lens of a brand strategist who searches for hooks to inspire consumers—the old notion of the American Dream is becoming less credible. In my own research with younger consumers I’ve heard anecdotal proof for the economic data above. Twenty and thirty-somethings tell me that they’re not convinced they will make a lot of money in their lifetime. They are skeptical about whether or not their 401(k) or investments will be there for them when they retire. They are unsure if they will be able to buy a house. In fact, many of them doubt that the other big American Dream—retirement—will ever happen for them. These beliefs are driving three patterns of behavior.

Life in the now

Amanda (not her real name) was born in 1985 and lives in New York City. She works for a media company and makes about $55,000 a year. She shares an apartment with two other women. She brings her lunch to work every day and takes advantage of her company’s many evening events to find free dinners several times a week. She also took a vacation to Belize in 2016.

Given what I know about Amanda, I asked how she could afford to take that vacation. First, I learned that travel to Belize is not as expensive as I imagined, but I also learned an important insight related to the next generation’s beliefs about money and lifestyle.

“The trip cleaned out my savings and made it a little harder for me to scrape together the next month’s rent, but it was worth it,” she said.

Previous American generations that believed in The American Dream practiced more delayed gratification. While Boomers proved they could run up credit card balances in the 1980s, they did so with a tacit belief that they would make enough money in the future to easily pay down those debts. But a good many Americans worked hard at their jobs hoping for the day they could retire and pursue their hedonic impulses—cruises, golf residences, world travel, etc. Their experiences before retirement were often moderated: they took the family to World Disney World because it helped the family do something together, despite the hit to savings. Such an investment was rationalized as necessary to family bonding.

This behavior is different than Amanda’s spending, which is more rooted in the notion that her present life may be as good as it gets and you might as well take some chances to feel alive now, today, this minute.

Life in the now is credited for many recent consumer developments. Last year I interviewed several experts in the spirits industry to understand the pronounced spike in whiskey sales amongst Millennials. Most of these experts described life in the now. These younger consumers might not be able to buy a nice bottle of wine, but they could afford an exquisitely crafted cocktail featuring quality bourbon or rye.

Best-selling author and entrepreneur Tim Ferriss established his own brand on the premise that people should enjoy the benefits of retirement today. The thinking has validated seemingly unusual choices by young consumers—like purchasing premium fitness classes (SoulCycle, CrossFit, Barre) when a traditional, less-expensive option would yield higher savings. The experience of living richly in the now matters more than the potential for living a rich lifestyle in the future.

Movement matters

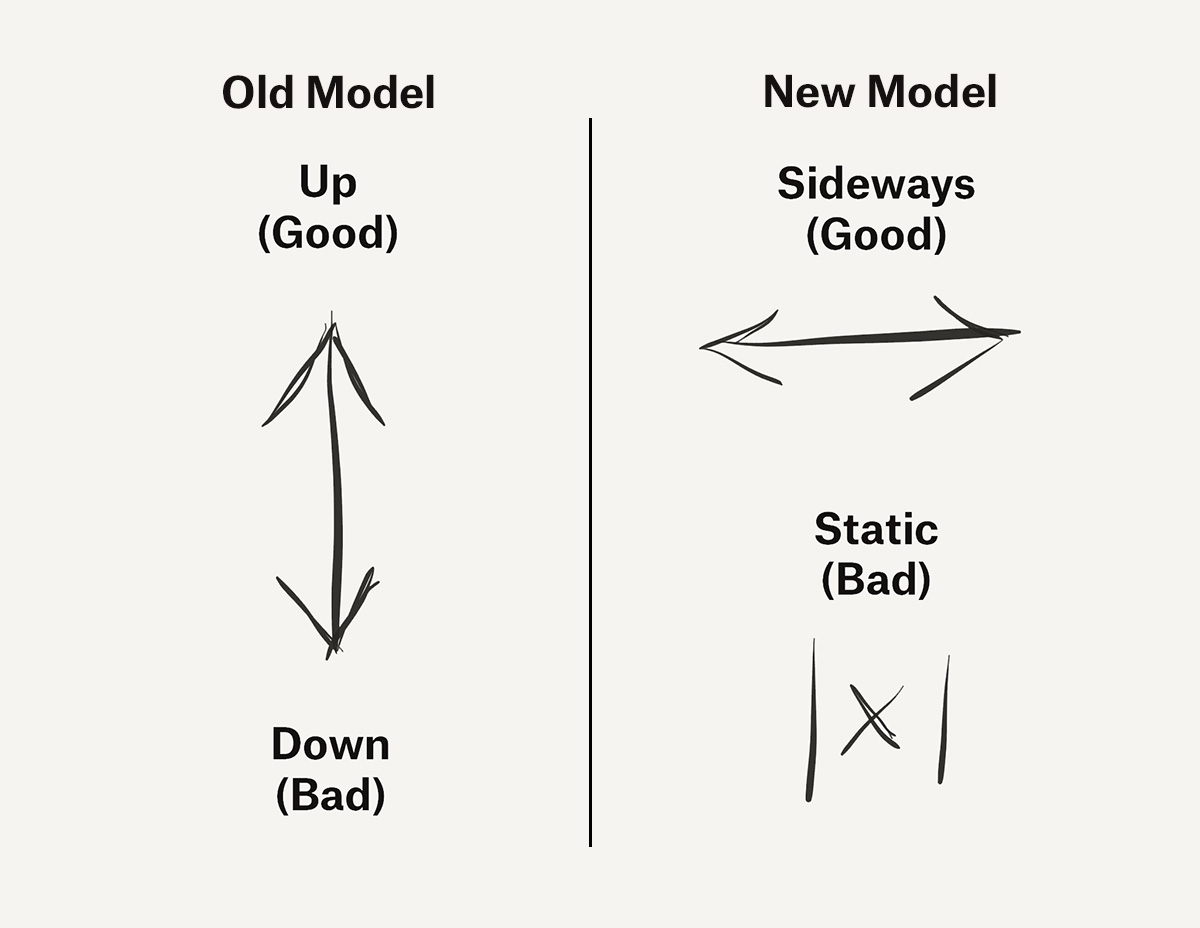

The classic American Dream rests on the premise of vertical mobility. Every American believes they can move themselves to a state of “higher” economic well-being. Up is good. Down is bad.

But the up/down metaphor feels out of reach to a growing number of consumers, so in its place we find the joy of lateral movements. You may not go up. You hope you don’t go down. But you’re perfectly comfortable moving sideways. That’s why the average tenure of next generation workforces continues to decline. There are no shameful feelings moving between jobs, sampling roles at the same pay grade, as long as you are finding the intrinsic benefits that lead to meaning. Work/life balance was once the domain of older workers who were feeling the stress of an upward mindset. Today 20-somethings talk about it as a key criteria for job satisfaction. It doesn’t necessarily mean shorter hours. In fact, many young workers who report feelings of positive work/life balance work long hours. They gauge their work/life balance according to the social environment of their workplace, the perceived opportunity to learn and grow, and alignment with their overall values and life goals.

Worse than moving down, economically, is the prospect of being static professionally. The new model is about motion over stagnation.

Fail fast

MTV surveyed the generation after Millennials to understand how they would like to be labeled. While no generation appreciates the labels marketers coin for them, this next generation had a valid complaint. Gen Z is a derivative label of a derivative label. First, there was Generation X (people born between 1965-1980), which in many ways perfectly described a mindset of a generation forced to follow the epic footsteps of Baby Boomers. But Gen Y (the less evocative label often used to describe Millennials) was unimaginative and merely a reference to the next iteration after Gen X. That makes Gen Z an even bigger disgrace. Can we, as marketers and demographers, not coin a word or phrase that captures the spirit of today’s youth? Are we so lazy that we’re content to exhaust the alphabet?

Fortunately, the MTV survey allowed these youth to choose their own label, and they gravitated towards Founders. The phrase makes perfect sense for a generation that has come of age when the last hope for economic mobility revolves around the allure of technology and startups. Mark Zuckerberg is proof to them that you can become a billionaire if you take matters into your own hands and hazard the risks of traveling well off the beaten path.

This generation has also been inundated with a fundamental belief in startup culture: the idea of embracing failure. The startup gurus preach the gospel of failing fast. They say it is better to rapidly try something that might fail rather than take the “safe route” of actions others have tried before with less risk but lower upside.

When the data signals that you are a coin toss away from matching your parents economic status, what do you have to lose by trying something radically different? The conventional path isn’t as promising as it once was, so why not try something perfectly unconventional?

This mindset will continue to drive Founders and perhaps most consumers in the future. We should expect to see more brands that draw consumers by demonstrating their challenger bona fides. We may even see more companies resorting to “hostile branding,” as Youngme Moon defined so well in her book Different. A hostile brand is one that has no qualms telling certain segments of consumers to stay away. It has no problem saying that it isn’t for everyone. In fact, hostile brands often reject the premise that the customer is always right. They’re more likely to say, “if this isn’t right for you, than you’re probably not right for us.” The recent state of American politics certainly hints at the potential rise of hostile brands.

What's a brand to do?

The American Dream may not be dying, but it is reformulating. With its central premise of opportunity for all being challenged by the realities of a mature national economy, American consumers are less likely to believe that they will ever own a home, retire self-sufficiently, or eclipse their parents in their lifestyle. The brands that will prosper under new definitions of the American Dream will grasp this harsh reality and address it head on. These brands will focus on products and experiences that offer a different set of benefits, such as the following:

- Rich, hedonic experiences—experiences that elevate feelings and create delight at this very moment. These experiences will not be throw-backs to the 90s when it was about “living large.” Instead, they will be highly layered and have symbolic as well as emotional value. They will make the consumer feel good about spending more than they thought they could afford because they validate their life experience today. And, of course, the best of these experiences will be highly shareable.

- Sampling will matter more. You might not be able to afford to buy a Tesla Model X, but you can purchase a ride in one through Uber. The value of the experience will satisfy as much as (if not more than) the value of possession. Brands that understand this subtle difference will win big.

- A distinctive point of view will push winning brands out of the middle. If there is one lesson we learned in 2016 (for better or worse) it was the growing dissatisfaction with political correctness. Brands that excelled in the past by aiming to please the masses will be more challenged in the coming years. Instead, we will see more brands that do one or two things exceedingly well and in a distinctive manner that may be off-putting to some consumers. The fail fast mindset will require many legacy brands to decide between alienating some of the audiences and increasing their overall profitability vs. playing it safe and decreasing their overall financial return. The latter strategy is actually quite dangerous, for it can create the opportunity for rambunctious challengers to invade and redefine established markets, placing the incumbent on defensive footing and making it look sadly dated.

- Some brands will succeed at redefining the American Dream by repurposing some of its core tenets (liberty, prosperity, innovation), but they will need to proceed with great caution. The brands that fall back on tried and true variations on these themes (diversity, inclusion, loyalty) may find themselves preaching to increasingly older and disengaged audiences. Too many Americans find these ideas to be a fantasy or a relic from another era.