Reading Time: About 3 minutes

Cocooning is a word that entered popular lexicon in 1981, coined by trend guru Faith Popcorn. While a novel concept at the time, four decades later it is a fact of life. Nowhere is this fact more apparent than in the leisure habits of Americans.

Executives in the media industry often talk about digital cocooning and shifts in viewing patterns, but a lot of that talk is anecdotal and relayed through hunches and personal observations. A good source of hard data can be found in the American Time Use Survey that is published each year by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. ATUS is a comprehensive breakdown of the ways in which Americans spend their time, with adjustments for weekdays, weekends and holidays. The data is used by economists, policy makers, social scientists and many others to understand everything from how much time we spend working at home to how much time we spend sleeping. One fascinating and often overlooked dimension of the study is the ways in which we spend our leisure time.

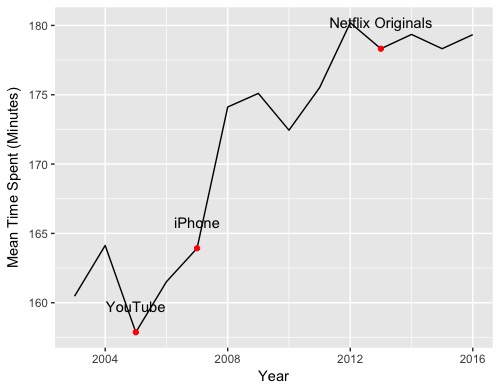

For those who say that we are living in the golden age of television, the data in ATUS supports your argument, at least in terms of media consumption. The amount of time Americans spent watching TV and movies from their home or some place other than a theatre grew almost 1% a year from 2003 to 2016. To put that number in perspective, attendance at movie theatres has declined by about 3% a year.

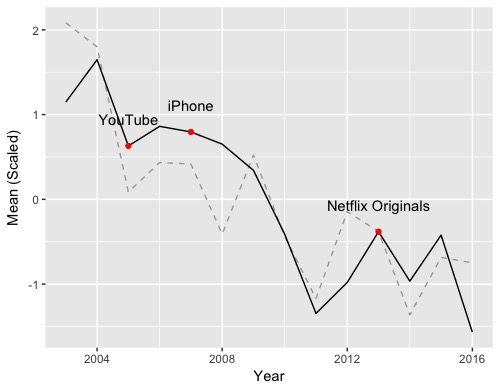

These numbers should not be surprising to anyone who follows consumer behavior. Mobile devices and better in-home viewing systems have weakened consumer demand for out-of-home entertainment experiences. In fact, the ATUS data reflect some significant turning points. For example, time at theatres plummets just a few years after the launches of YouTube and the iPhone. It’s worth noting that it is also very likely that this steep decline was related to the onset of recession in 2008. While time watching movies at theatres made a slight recovery in 2012, it dropped off again after 2013, which was coincidentally the year that Netflix released House of Cards, its first original series. While there is no statistically significant relationship evident in the data yet, the introduction of over-the-top film and television series offerings like those from Netflix, Amazon, Hulu, and now, Apple, should further erode the time consumers spend at their local cineplex.

Personal Viewing of Movies and Television Content

Time spent watching movies or television from a place other than a theatre

Going to the movies

Time spent watching movies at a theatre

(Dashed line is BoxOffice Mojo data on domestic tickets sold in same period)

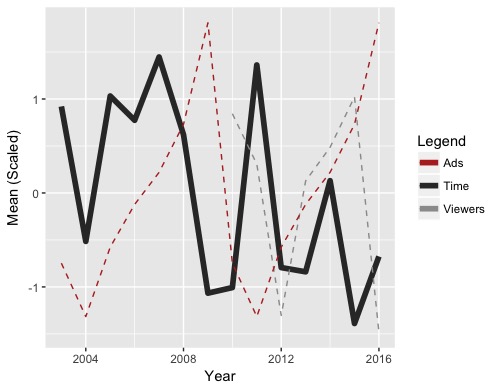

The ATUS data reveal some other fascinating dimensions about consumers and their leisure time. For example, they aren’t watching as much sports. Every major televised sport is down. That includes the NFL. Consumers began shaving off time for big league pigskin in 2008. Despite a brief spike in 2011, the time spent watching football has declined by about a 3% compound rate since 2003. As many media analysts have been reporting for some time, this trend has been reflected in Nielsen viewing data. As if to spite those viewers who still tune in, the volume of ads seen during an average NFL broadcast has steadily increased since 2011 (according to Nielsen and UBS).

Football patterns

Time spent watching Football vs comparable data on NFL

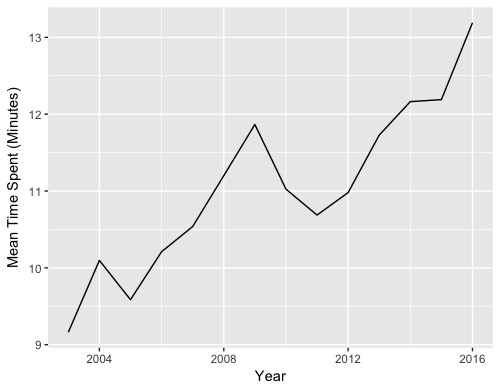

While they may not be watching the games of professional athletes as much anymore, they are certainly playing games. Video game consumption has been growing at a steady 3% pace. Much of that pace has been driven by the rapid rise of mobile games. Expect that to continue. The much anticipated iPhone X includes the A11 Bionic processor, which is specifically “designed to accelerate 3D apps and games.”

Video Gaming

Time spent playing video games

Sadly, the modern cocooning trend has one noteworthy drawback: We appear to be socializing less—about 1% less every year. On the one hand, it’s not at all surprising. Cocooning is a process of drawing in and away. It’s hard to socialize when you don’t go out. On the other hand, the rise of social media should, in theory, mean that we are socializing more in virtual ways—chatting and sharing from anywhere, anytime. That may be true. While the coding standards of the ATUS study have evolved since it was first implemented in 1991, it may be under-reporting socializing experiences that happen through digital channels. There is ample evidence to suggest that consumers are multitasking and getting more from their time doing things like socializing while playing a game, for example.

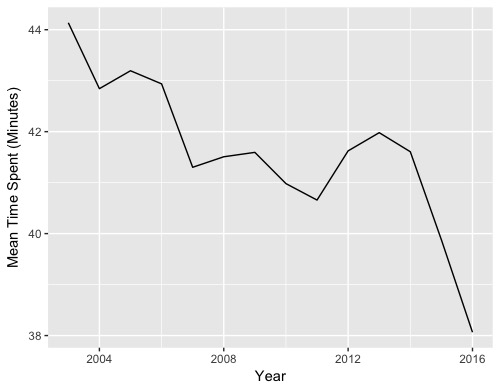

Socializing

Time spent socializing

I’m more inclined to believe that the under-reporting isn’t all that significant. As I sit in my home writing this, surrounded by my family, I can’t help but notice that each of us is immersed in a unique phosphorous glow—our digital Patronus—sitting together but not interacting. While social media has probably shored up the “real life” socializing that doesn’t occur because we’re going out less and less, it is not enough to keep us from getting lost in our leisure time, consuming a growing universe of content offerings and enjoying novel distractions alone.