Reading Time: About 6 minutes

In ancient times, during the prehistoric epoch when I was an MBA candidate (that would be the 90s), professors relied upon a handful of marketing cases that conjured a bounty of groans and eyerolls from students because of their ubiquity and repetition. One of these cases was Harley-Davidson and its disastrous attempt to respond to increasing Japanese competition in the 80s by making its roadsters lighter and quieter. Another was the case of the Walt Disney Company just before its rebirth in 1984 under the leadership of Michael Eisner and Frank Wells. That case unpacked the failure of Disney teams to understand the full demand and potential of Disney’s brand with audiences around the world. But the one case that we students tired of the most wasn’t about mice or motorcycles. It was about a failed attempt to change one of the world’s most iconic brands: Coca-Cola.

New Coke was introduced to the world on April 23, 1985. Within days, people were hoarding cases of “old” Coke, rationing out of fear that they might never again taste their favorite cola. The public outcry was so boisterous that two months later, the Coca-Cola Company relented and announced the return of Coca-Cola “Classic” to store shelves. For the next few years, Coca-Cola attempted to market the two products side-by-side before rebranding New Coke as Coke II in 1990, and then finally scuttling the Scrappy Doo of sodas in 2002.

Business school professors loved this case because it provided multiple degrees of analysis and fodder around what was then considered the biggest marketing blunder in history. In a classic case of not seeing the forest for the trees, Coca-Cola’s management team got lost in a share war with rival Pepsi and nearly imploded.

I don’t discuss this case much in my classrooms today. The few times I’ve referenced “New” Coke my students looked puzzled. It’s the same look that I receive when I make Love Boat references or frame competitive battles in terms of the Empire vs. the Rebel Alliance. These cultural inflection points all occurred before their time. Also, imagining an era when manufacturers of cola beverages went to war to steal 1% market share from each other seems quaint, especially during the present era when the most attractive career paths for students are to companies like Google, Facebook, and Amazon—all companies that hold monopolistic market shares.

Have no fear. The management team at Warner Bros/Discovery is about to remind us why “New” Coke is still relevant. Next Tuesday the company plans to rebrand its streaming service from HBO Max to Max.

The decision has already sparked significant debate among industry analysts and consumers. Many see it as a perilous shift away from a distinctive and established brand identity towards an uncharted territory of genericity. The renaming of HBO Max isn’t just a question of semantics; it’s a change with potential ramifications in branding, content bundling, and the future of cord-cutting.

It’s Not TV. It’s HBO.

In an increasingly aggressive turf war for premium content subscribers, HBO has been collecting fees from satisfied viewers since 1972, 13 years before Coca-Cola opened a can of New Coke on the world. HBO became the first network to deliver programming by satellite in 1975. When the cable television boom took off, HBO was consistently the most popular premium add-ons to the basic cable tier. Before Millennials were graduating high school HBO began a legacy of winning Emmy Awards for its own original content. By my count, HBO has earned almost 300 primetime Emmy awards to date. It won 38 of those in just the last three years. The awards were so consistent some television executives bemoaned HBO’s competitive advantage. It bequeathed a library of proven hits such as The Sopranos, Game of Thrones, Sex and the City, Six Feet Under, Oz, Band of Brothers, and my current obsession (see my last post): Succession. Honestly, you have no idea how hard it was for me to cull down the preceding list because there are so many beloved titles in the HBO library.

What is HBO, really? This existential question is one I almost always ask when working with a team of students, strategists, or clients: what is the brand? In HBO’s case it is certainly a badge of provenance. Like a Bordeaux wine, content made by HBO inherits a promise of quality, prestige, and authenticity. Viewers expect that a show made by HBO was vetted with a high bar and the risk of it being a waste of their time is low. But HBO is more than a maker’s badge. There are plenty of these badges in entertainment: A24, Amblin, MGM, and DreamWorks, to name a few. HBO has always been more than a slate. It was a destination. You went to HBO by changing the channel on your cable box or, until recently, launching its app. Going to HBO and being served a show vs. going to a generic, umbrella platform and watching a show made by HBO are not equivalent experiences.

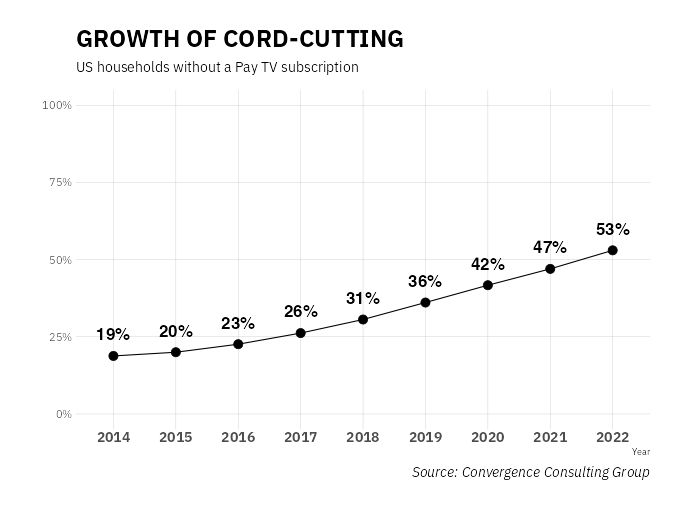

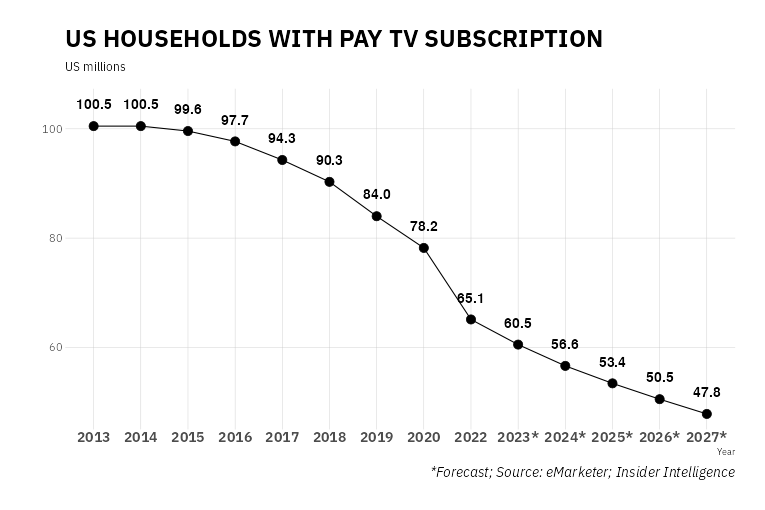

Do not underestimate the value of HBO’s destination-ness. Content destinations have created tremendous value for their owners and for consumers. True channel destinations created the demand for cord-cutting. Consumers rebelled against the practices of cable companies and satellite operators who held cherished destination channels such as ESPN, MTV, and HBO hostage through high, bundled service fees. The ransoming of HBO, in particular, created some of the strongest consumer activism. Most providers restricted access to HBO to those consumers willing to purchase a “premium” package that included several other channels the subscriber might not have wanted at all, such as Cinemax, Starz, and Showtime. The subscriber wanted HBO. To get it, they had to commit to an over-priced channel suite. There was no option to pick and choose.

Right at the very moment when consumers are finally getting what they wanted, Warner/Discovery is dialing back to an earlier time. If you want HBO going forward, you’ll have to stream on a platform that includes thousands of hours of Discovery Channel programming you didn’t request. Want to watch The White Lotus? It’s on the menu with Shark Week and Dr. Pimple Popper. Warner/Discovery sees this as a feature, not a bug. They view the Max brand as literally a value proposition of abundance. They’re missing the reality that their audience is not homogenous. It has many segments and some of those segments only want HBO.

Back in 2019, when HBO Max was owned by AT&T, AT&T President John Stankey declared, “we’re basically unbundling to re-bundle.” The question is why? The logic of the bundlers is simply that consumers don’t want multiple streaming subscriptions. There’s plenty of research to support this proposition. A study by Forbes Advisor earlier this year found that 86% of streamers subscribe to more than one service but 47% spend money on streaming services they do not use. Over 50% of streamers reported signing up for a streaming service just to watch one show. This last point hints at what streamers have wanted all along—the freedom to pay for what they want, and not more.

With HBO Max, consumers could anticipate a certain caliber and genre of shows and movies based on HBO’s past repertoire. It all fit. But the new Max doesn’t evoke a specific content association, implying that anything could be included—and it appears anything and everything is what Warner/Discovery plans to host under this tent. In a world already saturated with content, this lack of focus could lead to information overload, making it harder for consumers to find the content they truly want.

The Warner/Discovery team assures us that HBO is not going away. It will continue to be a maker of content and, at least as far as I can discern, the HBO and HBO2 channels on your cable or satellite menu will not be renamed to Max and Max2. But cable and satellite subscriptions are steadily declining. eMarketer forecasts that the number of households with a cable or satellite subscription in 2027 will be less than half of what it was in 2013. HBO’s prominence as a premium content provider is more critical than ever. Rebranding its streaming service to ‘Max’ while its fixed presence on linear TV reaches fewer and fewer audiences diminishes HBO’s presence and stature overall.

Simply the Best

I used to publish an annual study on brand attachment. In it, we asked people to cite a brand they could not live without. HBO was usually on the short list. Survey respondents chose it from a list of other media brands that included Disney, ESPN, Netflix, FOX, ABC, NBC, CBS, MTV, Food Network, HGTV and many other content brands. Each year HBO usually ranked #2 or #3 in our study (the top three were usually some combination of Netflix, ESPN, and HBO … this was before the Disney+ era).

HBO is a reference brand—a brand in a category that consumers effortlessly use to benchmark other brands. It was not uncommon to hear someone describe a program as something they’d expect to find on HBO, or “not as good as HBO.” Many industry analysts have recently referred to Apple TV+ as the next HBO. That’s a reference brand in action, but it’s also a nod to a more focused branding agenda. Less is more. For now, Apple is carefully curating the content that appears on its platform, and that content is purposefully premium.

Ultimately, the decision to rebrand HBO Max as ‘Max’ is a risky venture that might steer the platform towards obscurity rather than distinction. In a media landscape where specificity and quality content reign supreme, this move could very well be a step in the wrong direction. Warner/Discovery will need to ensure it navigates this transition effectively, lest ‘Max’ loses the prestige, differentiation, and content quality long-celebrated with the HBO brand.