Reading Time: About 7 minutes

Last Sunday I sat in a full house to enjoy an organ recital. It wasn’t at a quaint local church but at Walt Disney Concert Hall, one of Los Angeles’s most popular concert venues. The work was a new concertante by Essa-Pekka Salonen, Conductor Laureate of the LA Philharmonic. Based on the standing ovations that spontaneously commenced upon its completion, I’d say the audience was impressed. I know I was.

In a day and age when artists like Taylor Swift and Beyoncé are filling arenas on highly successful tours, it seems counter-intuitive that there would be much of a market for classical music, let alone works featuring pipe organs. Yet, classical music is having a moment. Writing for The New York Times, Maureen Dowd reported last week that attendance at classical music venues around the country has been on the rise since restrictions from the COVID-19 pandemic subsided. The demand has been so significant that Apple recently released a “brand-new standalone music streaming app designed to deliver the listening experience classical music lovers deserve.” It should also be noted that my concert experience was in the same venue where a recent attendee of a Tchaikovsky concert reportedly enjoyed a very-audible orgasm. To paraphrase an over-used Mark Twain quote, reports of classical music’s demise are greatly exaggerated.

It got me to thinking about another art form that has been unjustly pronounced dead before its time: writing.

On the train ride down to Disney Hall, I read the latest post from Scott Galloway. For the record, I’m a fan, though I sometimes disagree with “the big dog.” In this case, the disagreement was vehement. Galloway argued that the strike waged by the Writer’s Guild of America (WGA) against the Alliance of Motion Pictures and Television Producers (AMPTP) on May 1 was akin to the 1989 UK coal miner’s strike. He also argued that the WGA’s strike was destined to fail because of “structural decline” in scripted entertainment due to a “tsunami of alternatives.”

While I respect Galloway a lot, his opinion here doesn’t square with what I’ve learned working in the media and entertainment industry for over two decades, nor does it align with what I know about audiences. He is not the first critic to declare writers a dying breed, and he won’t be the last. Folks have been predicting the obsolescence of writing since Shakespeare’s time. And yet, every major advance in the history of commercial entertainment has one common denominator: writers.

Reality check

The crux of Galloway’s argument is that the public won’t care when striking writers lead to a short supply of scripted content. He posits that audiences will just watch more unscripted (or “reality”) television and shift their attention to social media platforms like TikTok. Many analysts have made similar arguments, using evidence from 2007/8 when the WGA went on strike the last time. That strike lasted for more than 100 days and during the work stoppage networks ramped up production of reality programming to fill the void on their schedules. What these analysts neglect to mention is that, while primetime television bulked up on reality programs, the ratings during that period fell 6.8% vs. the season prior.

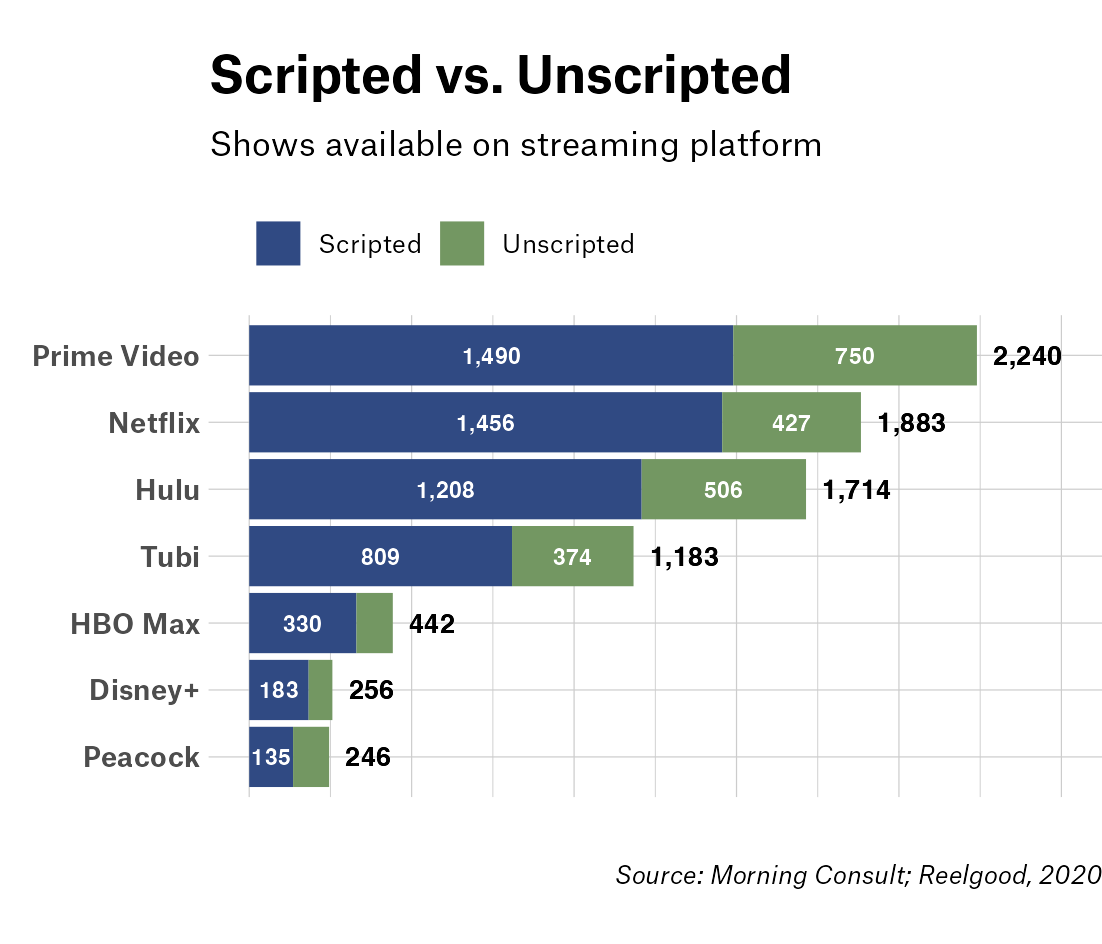

It also fails to recognize the era that started right after the strike–our current era, referred to as “Peak TV”–which has been largely defined by an abundance of scripted programming. This is the era that has gifted streamers with highly successful series such as The White Lotus, The Crown, Breaking Bad, Ozarks, and many, many others. In 2020, Morning Consult analyzed 2,240 TV shows that were available to stream across 140 US streaming platforms. Care to take a guess at the proportion of content that was scripted? That would be 68%, with the number increasing to 77% for Netflix and 70% for Hulu.

Do we have too much scripted content? Probably. Actually, the more correct assessment is that we probably have more than enough poorly scripted content. The divide between good and bad writing can be stark, and this is the reason uber showrunners like Ryan Murphy and Shonda Rhymes enjoy lucrative output deals and generous nine-figure compensation packages. The problem with good writing is that you only realize how much you miss it when it’s gone.

Here’s another spoiler for Galloway: some of the most popular unscripted television programs rely on well-compensated writers. What? That’s right. Reality shows have writing teams … not to tell the subjects what to say, but to devise situations that are likely to create conflict, because conflict equals profit. And while many reality shows might be able to get by without union writers, the truth is that unscripted content isn’t much of a substitute for scripted.

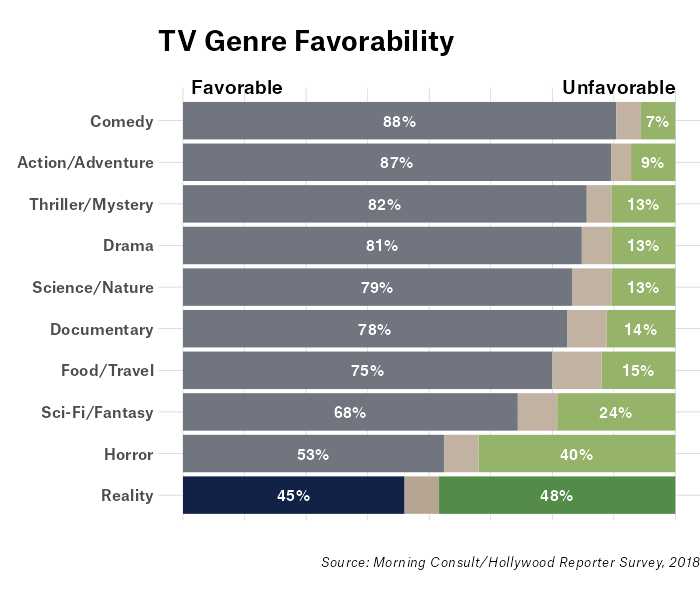

A 2018 study found that reality programming was the least favored genre. 48% of respondents had an unfavorable view of it vs. 45% with a favorable view. 62% of women in the study agreed with the statement that “there is too much reality television programming.”

Headwinds, Labor and AI (Oh My!)

Words matter and audiences love them, but the picture isn’t so rosy for the striking WGA because studios have anticipated the strike and stock-piled scripted content. If you are a fan of late night television, you’re feeling some discomfort right now, as all of those shows shut down on the first day of the strike. Most Americans haven’t noticed because late night viewership has been steadily declining. For everyone else, it will be months before we notice a shortage of scripted programs.

I actually agree with Galloway on one point: the strike comes at an opportune time for studios and networks. The content arms race has been incredibly expensive. In an effort to lure viewers to their platforms, producers have outbid each other for rights and talent. HBO’s House of the Dragon reportedly cost almost $20 million an episode to produce. The strike provides all content providers with an armistice that justifies laying off teams and retrenching on economics. But make no mistake, it’s only an armistice, not an end to the conflict.

I did several media interviews when the strike began. I was often asked what was different about today vs 2008. The answer is The Creator Economy. Social media was in its infancy back then. Today, it is arguably one of the dominant competitors for consumer attention. But Galloway’s argument that audiences will migrate to TikTok doesn’t square with the stats. Yes, teens and young adults spend a massive amount of time on social platforms. They are also the reason we have an incessant supply of movies built on the Marvel Cinematic Universe. The latter requires writers.

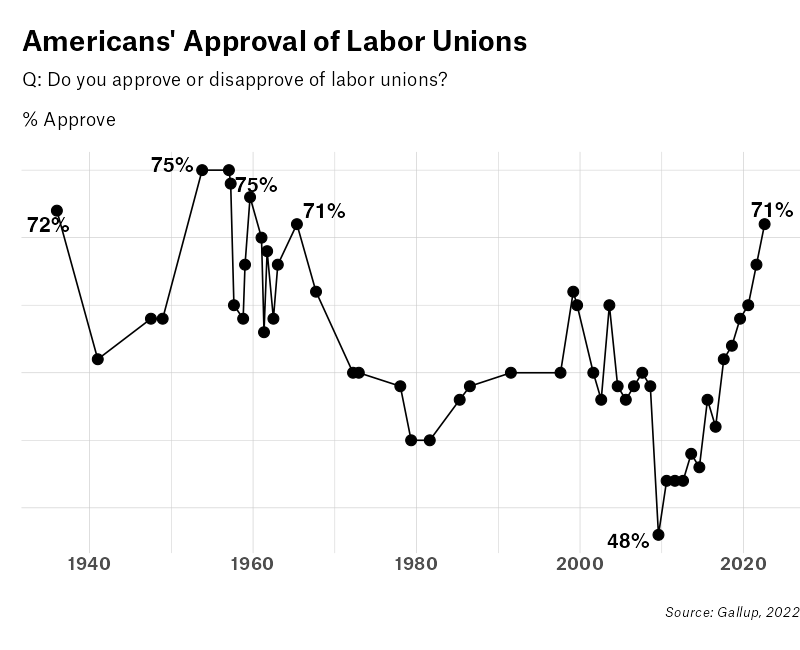

This is a good place to pause and suggest that the WGA might have some wind at its back. Gallup reports that public support for organized labor has been steadily rising and has reached a peak that was last recorded in 1965. It isn’t just writers and Amazon and Starbucks employees that are organizing. Social media influencers (a.k.a. TikTokers) are also mounting campaigns to organize. If there is one rule that is practically infallible in media and entertainment it is that talent always wins.

But Larry, you say, what about AI? Yes. I believe AI can probably write a Marvel movie (apologies to Marvel fans), but can it write The Crown, Succession, Ted Lasso? Not yet. Because these shows require something called nuance and awareness of the human condition, something AI doesn’t yet understand. What made a Harold Pinter play great? It was less about what characters said and more about what they didn’t. Ask AI to write a gut-wrenching, nearly wordless play. It will struggle because the AI of today is based on large language models (LLMs). This technology is nothing more than a predictive algorithm based on analysis of a massive amount of data. It’s predictive. But here’s the thing about great writing: it plays with expectations. We love the stories we didn’t see coming. Writers do more than give characters words to say. They develop stories that play with our imagination, that dig deep into our souls to find threads that are relatable to the life we know. Writers fill the space that comes after the question “what if…?”

It’s no secret that I sympathize with writers. Writing is an important part of my professional life and many of my closest friends are professional writers working in entertainment. I’ve watched as their job security has been compromised by reduced residual participation, truncated series orders, and studio shortcuts to the process of development. Add the boom in AI that surged in the past six months and it’s not hard to understand why 98% of the WGA voted to act now.

Writers aren’t coal miners. They’re the folks who always have and probably always will provide the source code for culture. They are not all created equal, and the real issue underneath the surface at the WGA is the great income divide between the highly demanded writers who sit at the top of the earnings and the thousands of folks who are just getting started and driving an Uber to make ends meet. Not enough has been written about this, but it is as much a part of the problem as shrinking writers rooms and the threat of android writring partners. Writing for movies and television is more than an exercise of talent. It is a craft and a trade that requires practical experience and the benefit of shadowing those who came before. That’s what’s being lost.

However, I am hopeful because audiences will ultimately decide the writers' fate. They’ll tolerate disruptions in programming schedules for a bit. They’ll adjust to AI-infused content. They may even wean themselves off of traditional forms of entertainment to spend more time on other options for their attention. But it will only take one, very well-written show to remind them why scripted content is worth their time and a premium penny. The next Sopranos or The Office– something brilliant, unexpected, and entirely conjured by imagination and collaboration. This pendulum has swung back and forth repeatedly over the past century of modern entertainment, and audiences always put their money on the scribes.