Reading Time: About 7 minutes

Marketers are in the business of hacking consumer behavior. We do this by aligning our activities with four psychological influences: memory, motivation, perception, and emotion. I’ve been particularly fascinated with the last two for the bulk of my career. Branding is about purposefully influencing consumer perception, and emotion is the most powerful driver. To paraphrase Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, we are an emotional species that happens to think, not the other way around.

My fascination with these forces led me to write my first book, Legendary Brands. I wrote it at the end of an era when people marveled at a select group of brands that achieved cult status. I was intrigued by how these brands connected to a belief system. My thesis was simply that, for some consumers, these brands were a kind of religion. They prescribed behavior and differentiated between the sacred and the profane, creating a virtuous cycle in which the brand and the consumer co-created artifacts, rituals, and meaning. I believed this was the start of a period in branding in which consumers were becoming more empowered.

Not everyone agreed.

Naomi Klein published No Logo in 1999, a masterful critique of this brand/consumer theology. Klein argued that brands enjoyed an unfair power dynamic in the relationship.

When we lack the ability to talk back to entities that are culturally and politically powerful, the very foundations of free speech and democratic society are called into question.

At the time, No Logo troubled me. I worked in branding but I also believed in free speech and democracy. I didn’t feel that one belief cancelled the other. Yet Klein’s treatise got under my skin and made me reflect on how brands appropriated and often misappropriated consumer beliefs. I always kept a copy on my bookshelf, a fact that once startled a colleague. When she asked why I didn’t try to hide it, I explained that I believed (a) it was a good book, and (b) opposing views are critical to understanding.

Two decades later, one could argue that social media responded to Klein’s concern. It has never been easier for consumers to hold brands accountable and keep their power in check. One could also argue that those same forces have rendered my youthful interpretation of brand religion as archaic, if not naive. Brands no longer trade in dogma. They aim for enlightenment but sometimes fall into a hell worse than Dante could have imagined. This is particularly true when brands pander in causes.

2020 may go down in history as the tipping point for brand-cause pandering. It was the year that George Floyd was murdered, elevating the Black Lives Matter movement to the center stage of cultural discourse. Several brands tried to align with the cause by adding the #BLM hashtag to their social media posts or within their advertising. It wasn’t always welcome. In The Customer Class, a podcast I produced at the time, my friend Beverly Jackson, who was then the head of Social Media at Activision Blizzard, expressed the sentiment of many detractors:

It’s not necessary for the company that makes socks to tell me that Black Lives Matter. I think it’s just “feet matter.” I don’t think it’s necessary for you to be involved in that conversation [on social media]. It isn’t necessary to state that. And you get into those cancel culture conversations when you engage in things that you don’t really need to be engaged in.

The company that makes my socks … what I really want them to do is to hire marketing managers that look like me. I want them to have people on the board [that look like me]. I want to see feet that look like my feet.

I’ll state it another way: don’t make cause the emotional driver of your sales pitch unless it is central to your purpose.

The Fuss Over Light Beer

Dylan Mulvaney is an actress and a social media personality who has attracted over 13 million followers on TikTok and Instagram. She also happens to be a trans woman. If you’ve been following the news then you probably know that she created a video promoting Bud Light on Instagram during March Madness. The timing coincided with the one year anniversary of her public transition to (in her words) “being a human.” A firestorm from the far right followed and Bud Light became the latest brand to burn in effigy in the culture wars. Following a growing boycott of its product, Anheuser-Busch CEO Brendan Whitworth issued a pseudo-apologetic statement, claiming the company “never intended to be part of a discussion that divides people. We are in the business of bringing people together over a beer.” It only made matters worse.

There are lots of “hot takes” on the sad series of events that followed. I don’t intend this to be another but, for the record, I think Mulvaney’s video was harmless in every way. It’s hard to make a case that she is a divisive public figure. Quite the opposite. She has consistently promoted community and inclusion. She gained millions of followers because of her optimistic outlook on life. She invited viewers to follow along with her on her transition–expressing great vulnerability as she shared her hopes and dreams as well as her fears and anxieties. Her authentic, kind, and thoughtful character is reflected in her response to the controversy.

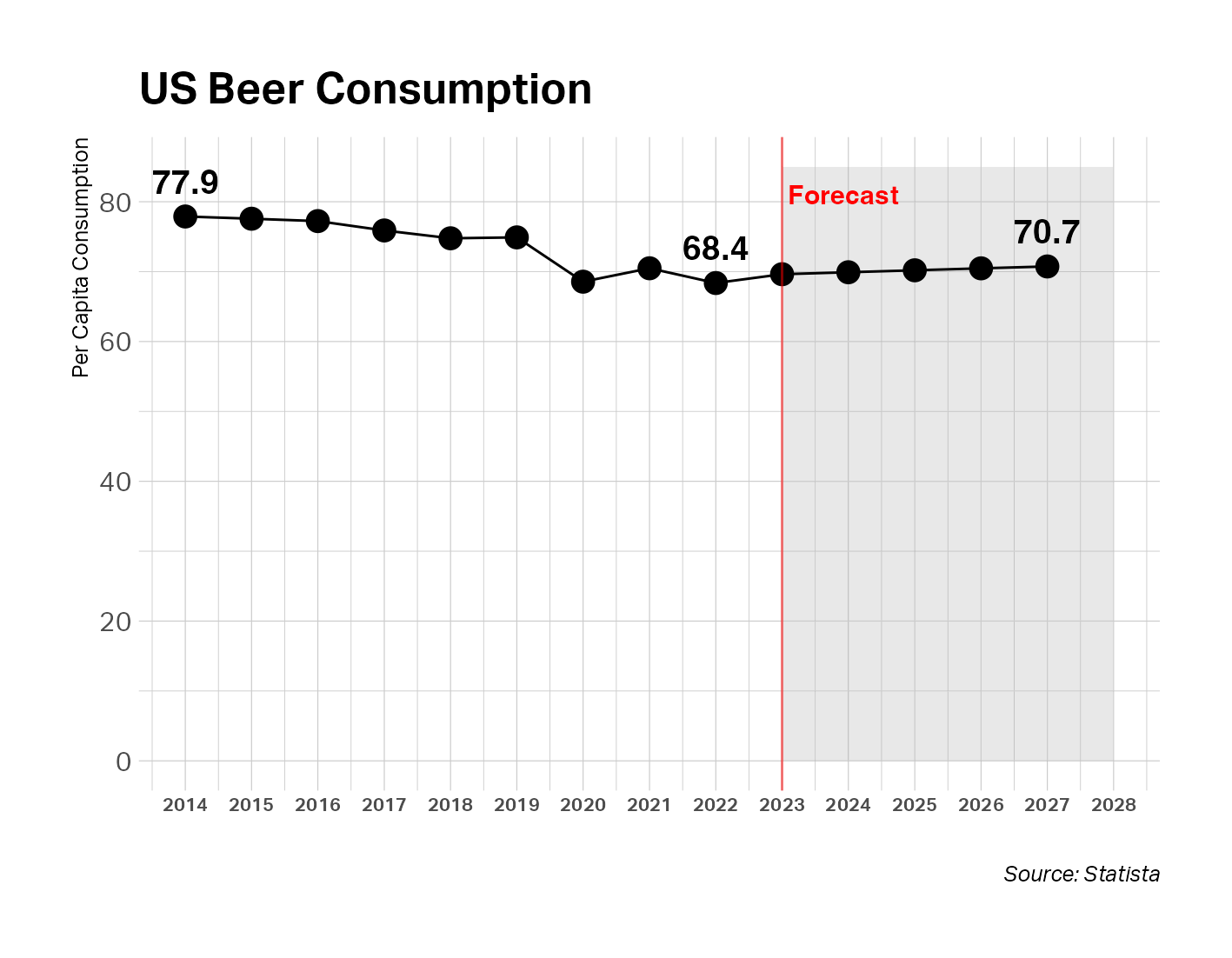

So, what was Bud Light’s intention when it sponsored her? I believe it was a growth-oriented segmentation tactic rather than an authentic alignment with a cause. Per capita volume of beer sales in the US has steadily declined. The little growth that is occurring is in the craft/premium segment, according to NielsenIQ. That’s not good news for Bud Light.

Worse, Bud Light’s audience is aging. The typical drinker is male and he’s over 40. The brand needs new blood to stay relevant. Winning Gen Z is critical for survival, unless Bud Light is satisfied becoming a niche, old school brand like PBR.

What do we know about the next generation of beer drinkers? Nielsen reports that 32% of the Gen Z audience believes “a product must be high quality,” which suggests that this generation’s tastes will probably gravitate toward premium and craft beers (see above). 28% “seek a recommendation from friends.” In this sense, the brand’s choice of Mulvaney was smart, as a perception of friendship is the root of the bond with her 13 million followers. Nielsen also reports that “Gen Z consumers care more about brand activism and engagement in social or environmental causes.” This would again support the Mulvaney activation, except that it leaves one important caveat out. Gen Z wants this activism to be authentic.

Some might suggest that AB had the requisite bona fides. Prior to the video’s release, the company had a perfect score of 100 on the Human Rights Campaign’s Corporate Equality Index, which rates companies on their policies towards workers in the LGBTQ+ community. The HRC removed AB from the list in May because of their backtracking on Mulvaney. HRC’s Eric Bloem stated, “Anheuser-Busch had a key moment to really stand up and demonstrate the importance of their values of diversity, equity and inclusion and their response really fell short.”

Lessons from a Cause Champion

Companies should not embrace a cause unless they are willing to fight for it. Contrast AB with Nike and their campaign featuring Colin Kaepernick, the NFL quarterback who made headlines by kneeling during the National Anthem to protest police brutality and social injustice. That campaign also instigated a media firestorm, saturated with images of angry customers throwing their Nike shoes into bonfires.

Yet, Nike did not retreat.

Kaepernick’s actions and values aligned perfectly with Nike’s principles. He didn’t give up even though his goal risked everything. Nike knew that the campaign would offend some customers and sales might suffer. Yet they also believed that more customers would be inspired than offended, and they were willing to risk profit for purpose. The decision to launch that campaign was calculated based on a mix of internal conviction and a thorough understanding of the potentially adverse economic outcomes.

Nike’s stock price rose 7.2% on the day the campaign launched. The Dow declined that day. Nike’s sales increased 10% that year. It put its money where its mouth was, and customers rewarded them.

Bud Light didn’t belong in the Pride conversation. It wasn’t willing to stand its ground, and that’s worse than being silent. It now sits in an untenable position. The Atlantic reported on Monday that Bud Light has lost its position as the share leader in the American light beer market for the first time in recent history. The irony is that it has been displaced by Modelo, an imported brand. After two months, the slumping sales show little sign of improving, with celebrity-endorsed boycotts persisting. Meanwhile, due to its backtracking, the brand has lost the trust of the LGBTQ+ community.

Full disclosure: I am not an unbiased observer in this story. I am a member of that community. As a gay man, and an Xer who came of age when the HIV epidemic drove many of us into the closet (my stay was so long that I had the closet renovated a few times), I find it disheartening to see brands retreating from the celebration of Pride. When I was the age of Gen Z, I never would have imagined so many mainstream brands would paint their logos with the colors of the rainbow in June. True: many of them return to grayscale in July faster than Dorothy returning to Kansas, but it has been meaningful to see brands I love willing to declare themselves allies, if only for a month.

This year, some of those same brands chose to step back because it might cause trouble. Bud Light gave them reason to pause. That saddened me. But, in a way, it may be good. The brands that continue to show their support will be the ones that are willing to stand by the cause, regardless of the potential backlash. Going back to Klein and No Logo, these brands can answer her question and provide the power of their platforms to let customers talk back.

Be it equality, social justice, climate change, the humane treatment of animals–really any cause that matters to consumers–the brands that will reap the benefits will be the ones that stand by their principles and prove perception is reality.